Synchronization between the body’s circadian clocks can prevent aging

“An experiment in mice reveals that a lack of coordination between the brain’s central timekeeper and the muscle’s molecular clock accelerates muscle tissue dysfunction. Reestablishing these communication networks helps restore proper functioning.”

“Night and day are not the same, not for the eyes, the liver, the skin or the pancreas.”

“The peripheral clocks — located in organs and tissues — receive this instruction from the central chronometer and regulate themselves to set in motion one function or another, depending on the time of day.”

“The deregulation of our clock is one of the clear characteristics that happens to all of us as we age. What we saw during aging is that the clock machinery, the basic one, the one that tells the tissue that it is this time or that time, that does not change. So if we wanted to find possible therapeutic ways to keep the clock in a young state in the old organism, we had to understand what happens to the clock.”

“The communication between the brain clock and the skin clock — are a step forward in understanding how these precise molecular devices work.”

“Human life is governed by a circadian rhythm (around 24 hours) that is controlled by a tiny biological clock located in the brain. Based on the light stimuli entering through the retina, this molecular device synchronizes itself and tells the rest of the organism the time so that it can act accordingly. Night and day are not the same, not for the eyes, the liver, the skin or the pancreas. The peripheral clocks — located in organs and tissues — receive this instruction from the central chronometer and regulate themselves to set in motion one function or another, depending on the time of day. Like a kind of orchestra in tune, all these molecular instruments that manage the circadian rhythms communicate, interact and work, in turn, with the necessary autonomy to make the organism function. This is how the gears of life work.

If those clocks that mark the rhythm of existence did not exist, aging would accelerate. This has been seen in mice: in functional studies, when animals were created without these molecular chronometers, they aged prematurely and died much earlier, as if a human died at age 40. In practice, the mice had all their genes, the capacity to express them correctly and perform their usual functions, but without these circadian clocks, they did not know the best time to perform these functions and the whole vital infrastructure ended up collapsing sooner rather than later.

These tiny chronometers are key to survival, but their modus operandi remains, to a large extent, a mystery: the scientific community knows they play a key role in the vital process, but is still trying to unravel how exactly these communication networks are configured between one another. New research published in Science and Cell Stem Cell by Salvador Aznar-Benitah, head of the Aging and Metabolism Program at the Barcelona Institute for Research in Biomedicine (IRB), and Pura Muñoz-Cánoves, researcher at Pompeu Fabra University, who recently joined the multinational firm Altos Lab, has shed further insight on how these molecular clocks interact with one another. In experiments with arrhythmic mice, the study showed that a lack of coordination between the brain’s central chronometer and the one that regulates timing in the muscle accelerates the aging of muscle tissue. Restoring these communication networks, however, makes it possible to restore the function of this area and preserve its activity.

This is the first time the researchers have successfully tested in animal models a hypothesis they have been forging for more than a decade: the idea was that, in order to maintain circadian rhythms, each tissue probably has an autochthonous rhythm, which is independent from the rest of the organism. And that there is another process of interaction with the clocks of other organs to synchronize functions. “It makes a lot of sense that if our circadian rhythm is preparing us for food, the tongue, gut, pancreas and liver are all synchronized to know that they’re going to have to start metabolizing food. Imagine the problems that could arise if the liver gets ready at 2 a.m. and the stomach at 1 p.m.,” explains Aznar-Benitah.

In the study published in Science, the researchers designed an arrhythmic animal model — with deficiencies in the central clock, the muscle peripheral clock, or both — in order to dissect which circadian functions were performed by the tissue independently and which depended on communication with other clocks.

“The deregulation of our clock is one of the clear characteristics that happens to all of us as we age. What we saw during aging is that the clock machinery, the basic one, the one that tells the tissue that it is this time or that time, that does not change. So if we wanted to find possible therapeutic ways to keep the clock in a young state in the old organism, we had to understand what happens to the clock. And what it is telling us is that a large part of what happens to the clock is not that the machinery isn’t working well, but that the synchronization with other tissues, both peripheral and central, are what have changed. And we had to understand in which part of the functions the tissue does not need communication, and in which part of the functions it does need it and with whom,” explains the scientist.

The experiment showed that in some daily functions, muscle tissue does not need to synchronize. “If you have an animal that does not have the clock except in the muscle cells, that muscle is capable of maintaining between 10% and 15% of its functions temporarily,” explains Aznar-Benitah. “What is basic, remains. And we think that there is an evolutionary advantage in that, because if all the functions of all the tissues were linked to one communication, if a person has an infection in the liver, there would be domino effect: if the liver fails, everything else would fail. The fact that these functions have been separated from the need to communicate and synchronize with others means that, even if a person has a heart problem, the skin maintains its ability to have a barrier,” says the researcher.

The study confirms that the coordination between the molecular clocks of the tissues is “crucial” to maintaining the general health of the organism. In fact, experiments to reestablish communications between these body clocks improved the condition of muscle tissue. One mechanism studied was to subject mice to temporary caloric restriction- they only ate during the active dark phase (night feeding) — which researchers discovered “could partially replace the central clock and improve the autonomy of the muscle clock.” Circadian restoration through caloric restriction mitigated muscle loss, impaired metabolic functions, and decreased muscle strength in old mice. “Eating like this strengthens the communication” between the brain clock and the muscle clock in mice, says Aznar-Benitah, although he clarifies that these findings cannot yet be extrapolated to humans — nor can the impact of practices such as calorie restriction.

In the skin, for example, time is key: the internal clock of this tissue knows that the best time to promote cell division of stem cells and regenerate the skin is when it is not in contact with ultraviolet light, which is mutagenic. If cell division occurs when the skin cells are exposed to UV light, they can be affected by mutuations and errors.

What’s more, because these cells are dividing, the mutations [they acquire from UV exposure] would be spreading to daughter cells, which would inherit that mutation. What the circadian rhythm does is separate these processes: it tells the skin cells not to divide while there is a peak of ultraviolet light,” says Aznar-Benitah. His study published in Cell Stem Cell, which analyzed this separation between DNA division and ultraviolet light exposure, revealed that if these communication networks between the central clock and the molecular timer in the epidermis are broken, cell division occurs at the same time as ultraviolet exposure.

Juan Antonio Madrid, professor of physiology and director of the Chronobiology and Sleep Laboratory at the University of Murcia in Spain, calls the research “beautiful and elegant because it describes many interactions and answers many questions” through “very interesting genetic engineering work.” “It is true that it is in mice, but it is interesting because it reveals to us how the body’s circadian system is not a hierarchical system, like a dictatorship, where the brain’s clock rules. It is more like a clock federation where everyone contributes.”

EL PAÍS

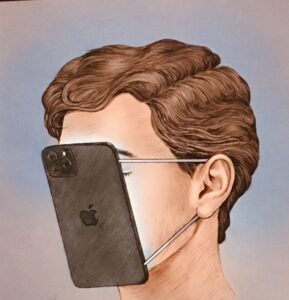

Addictions Hijack the Brain : from alcohol and tobacco, to junk food or digital content

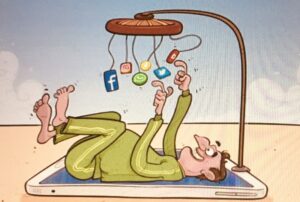

The algorithms are addictive. Who invented infinite scrolling? That’s addictive. The algorithms are a dopamine laboratory, which studies how to make these social media platforms more addictive.

Rubén Baler, neuroscientist: ‘We are guinea pigs. Our attention has become a profitable commodity’

He warns that overexposure to screens from an early age can have a negative impact on health

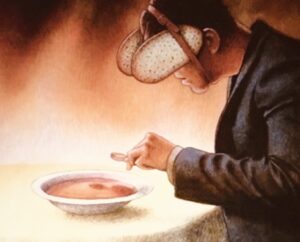

“Addictions hijack the brain, subduing it until it gives up on its most basic needs. Even eating and drinking — essential for sustaining life — are no longer priorities. But that substance or behavior that generates such brain dysfunction is usually just the symptom of a deeper phenomenon… the tip of the iceberg of a complex network of vulnerability and poor mental health.

Rubén Baler agrees with this assessment. He’s an expert in public health and addiction neuroscience at the United States National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA): “We need to worry about what’s important, not just about what’s urgent,” the neuroscientist warns. It’s not about the substances, but rather the phenomenon behind them. He assures EL PAÍS that there are hidden interests and hands that pull the strings of the dynamics that are harmful to public health. From alcohol and tobacco, to junk food or digital content, “there are increasingly powerful forces that have an interest in these products becoming more and more addictive and popular,” the neuroscientist affirms.

The brain is designed to identify what gives it a natural and healthy reward. When there’s something that increases our chance of survival, a little dopamine is released. we learn from the experience and are better equipped for the next time. It’s a very delicate mechanism, which works like a thermostat: between minimum and maximum values. Evolution designed a thermostat that’s regulated by dopamine, which is what regulates reward learning. Now, in the modern world, there are things that can skew the thermostat and push dopamine release values to [unnatural] levels. This artificial learning is an addiction. Each individual is a universe. This variation manifests itself in different vulnerabilities and [levels of] robustness. Interindividual differences are enormous, due to genes and life experience.”

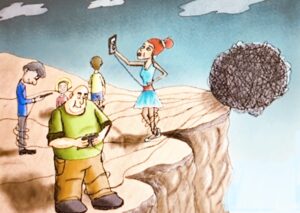

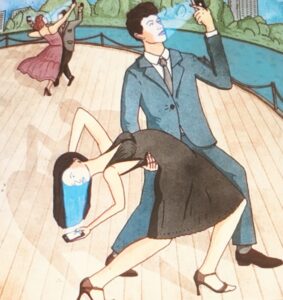

The algorithms are addictive. Who invented infinite scrolling? That’s addictive. The algorithms are a dopamine laboratory, which studies how to make these social media platforms more addictive. Especially for kids who gravitate so much towards social comparison — who depend so much on feedback from a community — all of this is extremely addictive and creates habits that are, in many cases, pathological.

We cannot depend on politicians, nor can we wait for scientists to save us. I think the solution is at the local level, in the schools. For now, parents can stop the use of screens in bed, because it affects a child’s sleep. That’s a vicious circle that leads them to get into risky situations… a lack of sleep alters the brain.I don’t understand why kids are allowed to bring devices to class, because that interferes with learning, class dynamics and attention span. It makes no sense.

We have to educate ourselves about how the brain works and [understand] that we’re being taken advantage of. We’re guinea pigs – commodities. Our attention has become a profitable commodity.

We’re paying a price voluntarily and the decision is up to each one of us. Either we’re zombies and sleepwalkers, or we take the reins of our own lives. Right now, we’re selling our souls to the devil, both our privacy and our brains. I understand how difficult it is, because this little device (he points to his cell phone) is everywhere and we depend on it. But we have to make an effort to see the good and the evil. We must try to take advantage of what it offers us for our well-being, while discarding the harmful effects of these technologies.

The epidemic started with prescription drugs (OxyContin, Vicodin, etc.). When we tightened the valve on doctors overprescribing these things, the curve of those prescriptions went down… and the curve of heroin began. When heroin started to rise, traffickers realized they could cut it with something much more powerful: they started creating fentanyl. Hence, synthetic opioids came along. Now, the fourth wave has to do with amphetamines that are cut with heroin and that appear mixed with fentanyl and a new drug — xylazine — which prolongs the psychoactive effects of fentanyl. But these are all symptoms.

We need to worry about what’s important, not just about what’s urgent. Why do people use drugs? What leads them to it? Misery? Hopelessness? Boredom? That’s what needs to be attacked. You have to look for the deep root causes.

There’s a financialization of the economy. There are groups that are very interested in the profitability of businesses: if we talk about junk food, these are industries that produce an incredible amount of profit, but the foods are addictive — they don’t help public health. [Digital content] platforms are addictive. The tobacco, cannabis, or alcohol industries produce enormous amounts of profits. And for the owners, for those who sit at shareholder meetings, the only thing that matters to them is the company’s profits… public health isn’t a priority. And, in that equation, the population will always lose. There are increasingly powerful forces that have an interest in making these products more addictive and popular.

Capitalism is the only system that works. I’m not against capitalism, but I’m against this form of overflowing capitalism that apparently has no sense of responsibility towards citizens. No brain — healthy or sick — goes back to the beginning. If brains are characterized by something, it’s constant change. Learning changes the architecture of the brain, but it can be good or bad learning. And addictions are based on learning through rewards. It’s like riding a bike: can you imagine a situation where you unlearn how to ride a bike? No. Because what was learned that way — with that intensity, in those learning trenches in the brain — cannot be unlearned. Addiction is the same: it will never heal, it won’t go away. The learning trenches are going to stay there. They can be covered with new, better, more passionate, more natural, more evolutionarily appropriate learning… but the trenches are going to remain. That’s why there’s always the risk of relapse.” El Pais

The emotional and spiritual effects of colors

Yellow furniture and decoration: Why not?

According to Goethe, yellow is associated with warm, joy and light.

“When applied to an interior, yellow is considered to be a great way to highlight a place, give it importance, draw the eye to it and emphasize that particular spot.”

Oh, were you one of those who thought that yellow was a cursed color, a color to be avoided at all costs? Well, that’s not true. Some people are so superstitious and negative and disapproving yellow. The legend, Moliére died on stage wearing that color. Update your perspective: yellow has arrived as one of the season’s decor trends, and it is fresh, unadulterated, and resounding; there’s no hint of shyness or any intention of hiding. In his Theory of Colours (1810), the German scholar Goethe discussed the psychological and symbolic aspects of colors at length, including yellow, which he associated with warmth, joy, and light.

Wasilly Kandinsky explored the emotional and spiritual effects of colors in his book Concerning the Spiritual in Art (1912); he argued that yellow radiates from the center and seems to approach the viewer and move out of the picture in an unsettling way that evokes delirium. Kandinsky associated colors with sounds and believed that yellow represented a trumpet or a bugle.

It is certainly difficult for this color to go unnoticed. In fact, it has traditionally (and effectively) been used on traffic signs to caution drivers; such visual warnings could easily replace a good trumpet blast. Michel Pastoureau, the author of The Colours of Our Memories (2010), says that his first memory of color is that of the yellow vest André Breton wore when he came to visit his father; Pastoureau was only five years old at the time!

Consequently, when applied to an interior, yellow is considered to be a great way to highlight a place, give it importance, draw the eye to it and emphasize that particular spot. On the other hand, the color is also useful in dark areas, since yellow adds luminosity to any location that lacks light.

Traditionally, yellow has been used with some trepidation, in small doses, as a little refreshing touch in the form of a decorative object like a vase, a cushion, or a blanket. That was an easy way to not let things get out of hand, to keep everything under control and not take risks. But now it seems that this caution is being thrown to the wind: many of the major furniture brands have opted to use the cheerful and lively yellow in upholstery and lacquering for good-sized pieces, from sofas to dinning tables to rugs.

Special mention should be made of three sofas in bold shapes that are reinforced by the choice of yellow: the monolithic Tortello by Barber Osgerby for B&B Italia; the Mr Loveland by Patricia Urquiola for Moroso; and the Bumper by Calvi Brambilla for Zanotta. The Telegram rug, by Formafantasma for CC-tapis, has the unique attribute of displaying words chosen by the artisans themselves as part of its design. And then there are tables like Sorvete by artist Joana Vasconcelos for the Bombom collection designed for Roche Bobois. A wide variety of different chairs also opt for yellow this season, including the stained-wood Zampa chair by Jasper Morrison for Mattiazzi, and the upholstered Romby chair by Gam Fratesi for Porro.

But let’s not forget that color perception is relative. One of the designers who has most studied that topic is Hella Jongerius, who created large, faceted surface objects that demonstrate how the experience of color and form is affected by the way light changes throughout the day: color responds to shape, texture and changing light conditions. Jongerius is particularly interested in researching weaving techniques and believes that, like color, textiles are layered materials. In her exhibit at the Boijmans van Beuningen Museum in Rotterdam, Netherlands, Hella Jongerius: Breathing Color, she explored the idea of chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul, who discovered in the 19th century that yarn colors are influenced by their environment and that colored threads in textiles are optically blended in the brain. Chevreul called this effect “simultaneous contrast,” a theory that has influenced many painters, including the Impressionists, who placed dabs of pure color side by side so that they blend optically in the viewer’s brain.

There are limitless shades of yellow, from pastel tones like canary yellow to more vibrant ones like lemon and ochre, mustard and gold. Depending on the hue one chooses, it will go better with one color or another. But in general, yellow goes well with grays, greens, blues and violet tones, which are its complementary color. Hicks, who left his mark on some interesting houses in the 1970s and is especially known for his bold use of color and patterns, knew a lot about distinguishing between shades. His granddaughter recalled driving with him in the countryside, surrounded by daffodils.”

El Pais

Are we getting tired of the selfie?

The surprising return of analog cameras

We’re seeing a recovery of the nostalgic, natural image

Researchers at the Boston Medical Center speak of “selfie dysmorphia,” referring to the disorder suffered by those who undergo plastic surgery with the purpose of looking like the version of themselves they see with social media filters.

We are tired of not being able to believe what we see, of being bombarded with messages that are not real and that generate toxic feelings for no reason.

“A generation used to unlimited access to information and tools is recovering the charm of objects that invite the opposite of smartphone’s immediacy. Interest in old-fashioned film cameras is increasing, especially for those whose childhoods are documented on film. “We take a lot of photos that last only until we change phones. But almost all of us keep albums from when we were little that are memories of our lives, places to return to and revisit,” say Cristóbal Benavente and Marta Arquero, managers of the Sales de Plata store, a stop for lovers of analog photography.

We are seeing a return to analog documentation of events: at festivals, people put away their cell phones and take out a disposable camera instead. Only once the film is developed does one encounter the final result, which becomes a treasure. Film photography is synonymous with beauty, melancholy and memory. It is also a limited service: since a film roll is not infinite, it forces photographers to choose with precision the moments to capture, creating an emotional bond with the subject, something which has been lost with smartphones. “Currently, we have images of absolutely everything we do and experience, whether it has value or not. Now, your wedding photos are interspersed with the image of the toast that you had for breakfast the previous week,” reflects Clara Sanz, Social Media Strategist at the creative agency Porque Pasado.

Restructuring priorities

Normally, after taking a selfie or asking for a photo for a potential social media post, there is an almost obsessive scrutiny of all the supposed defects of the face and body. This image is studied from all angles and, on some occasions, editing and filters are used, modifying the people who appear in it beyond recognition. Researchers at the Boston Medical Center speak of “selfie dysmorphia,” referring to the disorder suffered by those who undergo plastic surgery with the purpose of looking like the version of themselves they see with social media filters.

Alternative social networks like BeReal, which was born in 2020 to fight against this lack of reality and the complexes that derive from Instagram and other applications, offer a less artificial option. Members of Generation Z, who have shown a clear concern for mental health, have embraced them. But, as Clara Sanz points out, “from the moment you can choose the moment to take the photo and you can repeat the image, it loses a bit of its meaning.”

Analog photos may not be perfect, and everyone may not look their most attractive. But they capture the memory of a certain moment and what it felt like then, as well as a window to understand how others see: “Analog photography is authenticity and reality. It’s seeing your birthday photos around a cake with a stain on the tablecloth. It is having chocolate on your cheek and remembering how much fun you had at those parties,” says Sanz.

These imperfections are what millennials miss so much. The youth of Generation Z long for what they never experienced. The rise of analog cameras comes as a response to the need for naturalness lost after so many years of feigned perfection. Photography once again becomes a means of expression and a tool to materialize memories. In the case of disposable cameras, there is also the added attraction of not knowing what the result will be like until the roll is developed, which for many young people is a totally new experience.

The owners of Sales de Plata say that they receive a lot of questions every day regarding the management and characteristics of cameras, since many people who are curious about the subject have never had contact with it before, not even as children. “The curious thing is that the question is very common among older people: does this still exist? There is a great difference in perspective according to age regarding analog photography: those who see it as a creative medium full of possibilities and those who experienced its decline in the early 2000s, sold all their equipment and feel that it is obsolete,” say Benavente and Arquero.

Nostalgia without filters

There are countless photo editing tools that create a vintage look. This fixation has existed for a while. Many young adults now remember those teenage years when they spent hours in front of the computer screen visiting Tumblr accounts where this aesthetic reigned. It was common to want to live inside the music videos for Lana Del Rey’s Video Games and Summertime Sadness, which were suffused with the romanticism of home videos, found footage — fake documentaries— and, in general, a nostalgic, dreamy atmosphere.

“Going back to the past means returning to comfort, to the familiar, to the place where one feels safe. Perhaps this explains why there are now young kids taking photos at trap concerts with cell phones from years ago and taking the trouble to transfer these photos to the computer. Or people shooting video clips with MiniDV cameras. It is the same type of nostalgia that Wim Wenders includes in the film Paris, Texas, scenes from years ago in Super 8 films: it takes us back,” conclude Benavente and Arquero.

Hashtags like #filmphotography have over 40 millions followers on Instagram. In videos on social media, couples imitate photographs of their parents when they were their age, filling social networks with flashbacks to the 1980s and 1990s. “People want to feel natural again, to have references on which to base ourselves without fearing that everything is false. We are tired of not being able to believe what we see, of being bombarded with messages that are not real and that generate toxic feelings for no reason. I think it is a trend that should be maintained and promoted by all creators and that would give them added value,” says Sanz regarding the trend of images taken with analog cameras on social networks.

The analog camera industry experienced an evident decline with the arrival of digitalization. In 2012, the journalist Ramón Peco wondered in an article in this newspaper whether analog photography would survive. “It may seem like a romantic statement, and it probably is, but we must not forget that the photography business fuels many dreams. And for some, those dreams cannot be captured with digital technology,” he reflected at the time.

Maybe that is the crux of the matter. Charlotte Wells manages to capture all that melancholy with Sophie’s home videos in the film Aftersun. It is not a coincidence that a film about memory and the survival of images in the brain revolves around those files, nor that the memory of Sophie’s last night with her father in Turkey is an instant photograph taken with a Polaroid. That crucial moment, materialized with an analog camera, is physical proof that all those scenes existed, even though they are now blurred and confused with those in your mind. The Polaroid stops being an image and becomes a treasure, something that can still be touched when everything else is gone.

As Y2K becomes fashionable again, so has the use of digital cameras. Surely many millennials remember carrying one in their bag alongside their keys or mobile phone, as well as arriving home after a gathering with friends or a trip, plugging it into the computer and downloading all the photos. They may remember the flash that dyed the eyes red and the skin nuclear white. Now, social media influencers are recovering those cameras: they may appear in videos in which current couples imitate their parents’ photos, filling Instagram with a retro aesthetic thanks to digital cameras.”

EL PAÍS

The dark web’s two faces:

Charity fundraisers alongside extortion and kidnapping

“The well-known web we access daily through popular browsers represents just 5% of the internet. It’s just the surface of the deep web ocean of information that is intentionally hidden or not meant to be easily accessed.”

“90 million cyber attacks worldwide, costing $11.5 billion

Internet criminals, responsible for 84% of global scams, uphold codes of conduct and an arbitration system to govern their society

“The dark web harbors a wide range of sinister activities like murder for hire, weapons and illegal drugs for sale, distribution of child pornography, as well as robbery, kidnapping, extortion and infrastructure sabotage. It represents the most nefarious recesses of the internet. Yet even this criminal realm lives by a set of norms and rules. “They have their own code, although we must never forget that they are criminals,” said Sergey Shaykevich, director of Check Point Software’s Threat Group during CPX Vienna cybersecurity summit. “84% of all scams happen online,” said Juan Salom Clotet, chief of Spain’s Cybersecurity Coordination Unit (Civil Guard). This same dark web organizes charity fundraisers, celebrates holidays, disciplines inappropriate behavior and has its own “judicial system.”

The well-known web we access daily through popular browsers represents just 5% of the internet. It’s just the surface of the deep web ocean of information that is intentionally hidden or not meant to be easily accessed. Kaspersky security researcher Marc Rivero said, “The deep web covers anything not picked up by regular search engines, like sites needing logins and private material. On the other hand, the dark web- a slice of the deep web – is all about using hidden networks to keep users and sites anonymous. It’s commonly associated with illegal activity.”

“The deep web serves both legitimate and questionable purposes,” said Rivero. “It includes secure communication platforms for sharing information, uncensored social networks and support groups. It grants access to restricted data like academic or government documents, specialized forums for knowledge exchange, and entertainment sources such as digital marketplaces, gambling sites and online gaming platforms.”

Living on the deepest ocean floor of the deep web is a small criminal network that, according to Telefónica Tech’s María Jesús Almanzor, launches “90 million cyber attacks worldwide, costing 10.5 billion euros [$11.5 billion]. If cybercrime were a country, it would rank as the world’s third largest economy, after the United States and China.” Shaykevich researches this part of the web using “isolated computers and technical precautions” to defend against the rampant malware there.

To access the deep and dark web, browsers like Tor, Subgraph, Waterfox and I2P are used. Tor (short for The Onion Router) functions by connecting randomly to an entry node, forming a circuit of encrypted intermediate nodes for secure data transmission. The traffic within the circuit remains anonymous, with the entry and exit points being the most vulnerable.

“Tor was not designed for crime,” said Ghimiray, but criminals quickly recognized and leveraged its capabilities. Silk Road was one of the first. The dark web marketplace was created by Ross Ulbricht in 2011, and was shut down two years later by the FBI. Ulbricht, also known as Dread Pirate Roberts, is now serving a life sentence for money laundering, computer hijacking, and drug trafficking conspiracy.

“Accessing the dark web isn’t technically difficult – just download a specialized browser. But it’s risky. All sorts of malware, scams and more lurk there. Be cautious, protect yourself with security software, a firewall and a VPN for privacy,” warned Rivero.

Shaykevich says that accessing the dark web’s sewers typically involves an “invitation from a criminal mafia member or undergoing an investigation by them.” Rivero elaborated: “Some forums are public, allowing anyone to register, while others are exclusive and involve a strict selection process. Usually, methods like invitations by existing members or administrators are used, relying on recommendations from within the community. Some forums may ask users to fill out an application or undergo an interview to assess their suitability. Others might require users to demonstrate knowledge on a specific topic through exams or test posts, or be recommended by reputable dark web users.”

Once you pass these tests, the underworld of the internet is surprisingly similar to the rest of the world. “They’ve got their own chats and even use these hidden Telegram channels to hire services or show off what they’ve done, putting the names of their victims out there,” said Rivero. He also described an arbitration system used to resolve user disputes, like the one that dismantled the LockBit extortion group after it failed to equitably distribute the ransom from a kidnapping. The dark web forums held a trial, heard an appeal and issued a final conviction. “After that, it was really tough for them to work again because they lost their credibility, which is key in the dark web.”

In the underworld, you can easily find data belonging to regular internet users (Google One will check if your accounts are compromised or available on the dark web). The web pages tend to be simple, since no marketing strategy or search engine optimization is needed. The dark web also has user forums and chat apps like the regular world.

Shaykevich remembers Conti, a kidnapping and extortion group that supposedly disbanded after a leak. They once had “200 people and physical offices in Moscow. We analyzed leaked chats ranging from notices about freshly painted doors, to warnings about discussing malware in the building’s cafeteria.”

“The dark world is not that different from the real world,” said Shaykevich. “They throw parties, go on vacations, and even raise money for orphanages. They’re just people – yes, criminals – but they’ve got kids and some think they’re moral people. Some ransomware crews absolutely refuse to hit hospitals, and also steer clear of ex-Soviet countries. But let’s not forget – they’re still criminals.”

Attacks on institutions like hospitals are considered highly reprehensible in a world where successful robberies and kidnappings are used as part of publicity strategies. “Being a hacker is like running a business without integrity. They kidnap and extort people. But the worst is when they target a hospital, because they can kill people. And it’s all for money,” said Check Point VP Francisco Criado.”

EL PAÍS

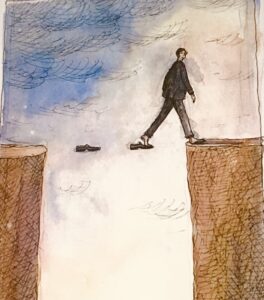

Main Key to Happiness: Willpower

Those who understand the importance of making efforts will build up strong self-esteem and will be able to overcome the bumps that come their way

“Efforts and perseverances should become the backbone of the education.”

“We live in a society where achieving anything appears easy. Where everything seems affordable, and people can get everything they want with a click of a mouse. Where we seek instant reward but talk little about error, frustration or effort. This misunderstood success leads one to think that we can achieve things without putting our soul into it, and that strokes of luck determine what one is capable of achieving or not. For families, when raising a child, effort and perseverance should become the backbone of their education. Teach them that their success in life will not depend on their ability to accumulate content or procedures, but rather on their ability to work hard and not give up when things get complicated.

Willpower is the ability to focus our attention and effort on something to achieve a goal. The habit that allows a person to move forward with perseverance when things get difficult, when a setback or a bad result sends their motivation plummeting to rock bottom. Willpower is a force that brings you closer to what you want, that deafens excuses and gives you the power to achieve what you don’t have, thanks to work. Perseverance provides stability and resistance in the face of setbacks, confidence in oneself and also in others, and large doses of self-esteem.

From a very young age, a child must learn to make an effort to get what they want because throughout their life, they will have to face numerous uncomfortable and complicated situations that will make them doubt their abilities. A child who integrates perseverance and willpower into their daily life will grow by building a positive self-image and will be able to overcome the stumbling blocks in their path. They will ask for help when they need it without feeling ashamed, and will understand that mistakes are an essential part of the learning process.

On the contrary, a child who does not develop perseverance and ability to put in effort will find it difficult to tolerate frustration and understand that mistakes are an essential part of learning. They will tend to blame others for their mistakes and depend on the adults around them to get what they want. They will be an insecure child with little personal initiative.

Teaching a child to get what they want with dedication and patience will turn them into a brave and autonomous person who wants to explore their environment freely and without fear, who wants to make their own decisions and take responsibility for their choices. If parents overprotect their child to prevent them from becoming frustrated or disappointed, they will only be preventing the child from acquiring the necessary skills to be able to face their difficulties with tenacity and confidence. They will turn them into an insecure child who is unable to cope with their problems.

Keys to educating a child on the importance of perseverance and effort:

- Help the child to set small daily challenges that are achievable, to commit to themselves without doubting their worth and work. You also have to help them design the program by planning each of the steps they will have to take to achieve what they propose, being aware that, throughout their life, they will have to overcome many stumbling blocks.

- Get them to understand and accept that they will make mistakes on their path, and that there is nothing wrong with that. Being compassionate with themselves when there are setbacks and learning from these moments will teach them how to move forward, little by little in their projects.

- Teach the child to be patient and to understand that much of what they want to achieve is done through work and effort. They must learn to postpone the reward until they have fulfilled their commitments and not to depend on chance or fortune, but on work and commitment. They must be taught to understand success as the ability to enjoy everyday life, to be grateful for everything good that happens to them.

- Demonstrate by example, with words of encouragement and affection that shows you are by their side, supporting them unconditionally, without judging their mistakes. Help them to properly manage and express emotions, to master impatience and indecision, to overcome bad moods when things go wrong.

Perseverance and willpower are the foundation for building the dreams we long for. A child who is capable of striving and working to achieve what excites and thrills them will build up determination, curiosity and optimism. They will show commitment without procrastinating or making excuses for bad luck or blaming others for their own setbacks. As the German physicist Albert Einstein said: “There is a driving force more powerful than steam, electricity and nuclear power: the will.”

El Pais

We cannot normalize having 10-year-old children working as influencers:

The challenge of controlling underage content creators

The problem is linking happiness to that idealized physical image, as that only leads to frustration.

Psychologist Lorena González: “We cannot normalize having 10-year-old children working as influencers. It should be penalized…Children learn what we teach them. We are their role models. If parents normalize this online overexposure, then this will be normal for them, although we still do not know the consequences.”

“Some of the influencer children of the Alpha generation — those born after 2010 — have more millions in the bank than years of age. They have acquired world fame on platforms like TikTok because they speak, make themselves up and dance just like the influencers they have been mimicking all of their lives.

One recent example are the so-called Sephora kids: this trend has filled the social networks with videos featuring hundreds of 10-year-old girls who get their hands on as many of the brand’s makeup products as they can to do skin care routines for their followers.

Garza Crew’s TikTok account has 4.9 million followers. The videos, made by her mother, show her as a 7-year-old American girl who, baby teeth and all, presents her makeup routines and the products that she buys like a professional. She also takes the time to talk about what it means to be a Gen Alpha influencer: “Of course we are obsessed with skin care. Of course our favorite stores are Sephora and Ulta. Of course we don’t have toys.” The star of the Garza Crew videos claims that she has been buying makeup with her sister, who is the same age, since they were both six years old. All her videos are monetized.

In September, Forbes magazine published the ranking of last year’s top creators, “the social media stars turning followers into fortunes.” On that list stands out 9-year-old Ryan Kaji, who went viral reviewing toys. Thanks to his 36 million followers, he made $35 million in 2023. His family has turned his online influence into a company called Ryan’s World that sells toys, board games and clothing, and he has already surpassed social media queens like Chiara Ferragni and Monet McMichael.

Cintia Lopez Narvaez , 36, has been a content creator for 12 years. This Spanish influencer first started with a fashion blog before migrating to Instagram, where she showed the outfits she wore to work. However, after her children were born, she decided to change her strategy: now her account revolves around motherhood and children. “I’m doing much better with this type of content; my community has grown a lot,” she says. Her six-year-old son Jorge has starred in campaigns for brands with her since before he can even remember.

López assures that he does it of his own free will. “First I ask him if he feels like doing it, and we always do it as if it were a game.” She has already lost count of all the brands she has worked with, but she does remember that everything, from the diapers to the children’s room, were collaborations.

The son has learned from the mother by imitation, and is already making videos of himself mimicking what he has heard her say thousands of times: “Follow, like, and don’t forget to activate the notifications.” López believes that soon Jorge will have his own content creator account — and she is fine with that. “For them it is normal, because they have been in contact with social media all their lives. We had to learn it.”

According to the study Generation Alpha: The Real Picture, published by GWI, in the United States the Alpha generation has influence and purchasing power beyond their age. “Around a third of teens have a bank account they can access,” states the report. In it, the researchers conclude that these children also have a higher social awareness from an early age and that they will become consumers of big brands earlier.

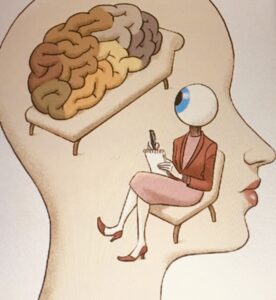

It is all the result of many, many hours of screen time. “Without a doubt, it is the youngest who spend the most hours glued to the screens, which in some way end up educating the children,” says psychologist Silvia Álava, author of the book Queremos hijos felices (in English: We want happy children). “The people that children follow on social media often show unattainable realities with which they compare themselves: the body, luxuries and diet could be affected by overexposure to social media in an unhealthy way.”

The problem is linking happiness to that idealized physical image, as that only leads to frustration. Facebook research leaked in 2021 showed that social media influences the mood of young people: more than 40% of Instagram users said they did not feel attractive while using the app.

Psychologist Lorena González, CEO of Serena Psicología, a clinic that focuses on women’s well-being in Madrid, Spain, sees how mothers come to her office every day worried about their children and social networks. “We have many examples of children who were famous at a very young age starring in films, and we have been able to see how at that age they don’t understand that the reinforcement that fame provides is not real, and that having millions of followers is nothing definitive. The broken toy syndrome is now being transferred to young influencers who live for their likes,” says the expert. Her opinion on the new phenomenon is emphatic: “We cannot normalize having 10-year-old children working as influencers. It should be penalized.”

The phenomenon did not spring up out of nowhere. The children of the Alpha generation, explain the experts consulted, have internalized what they have been taught since they were in the wombs of their millennial mothers, who have exhibited their children’s lives on their social media accounts from the day there were born. “Children learn what we teach them. We are their role models. If parents normalize this online overexposure, then this will be normal for them, although we still do not know the consequences,” says González.

Sheila Tabernero, 42, runs the Instagram account Palabra de madre (in English: Mother’s word), which has 58,300 followers and focuses on family leisure activities. She started in 2012 when she became pregnant with her first child, doing a blog about her experience with motherhood. Little by little she evolved, and when the second child arrived she began to talk not only about pregnancy, but also about issues of being mothers and family. “I entered this world of content creators and brands began to contact me, and that’s when my whole family and I began to collaborate,” says Tabernero, who is represented by the influencer agency SP Talents.

Tabernero explains that her three children have appeared on her social media accounts since they were born. “For them it is normal. As they have grown, especially with the eldest, who is 11, I have tried to be increasingly careful with their image,” she says. Although most of her videos are about family trips, where they appear in very natural situations, she does ask for her children’s input. “I always ask them before posting if they agree with the content they are going to appear in. In my house, my children fight because they want to be in my videos and collaborate with brands. If it were up to my oldest son, Ares, he would have gotten his own YouTube channel a couple of years ago, but I still don’t want him to,” she points out.

For psychologist María Padilla, this generation will usher in a paradigm shift: “It’s a generation that lives in a world dominated by digital technologies. These are children who have never known a world without the internet, smartphones and tablets.”

Social media expert José Alvargonzález resorts to the data to explain the situation: “TikTok has experienced exponential growth among young users. Recent statistics indicate that a considerable percentage of its user base is made up of children under 16, who spend on average a significant amount of time on the platform each day.” Hence the cost: “It is key to consider the impact of social media on child development. These platforms can foster creativity, personal expression and communication skills in children, but on the other hand, there are associated risks such as exposure to inappropriate content, self esteem problems and pressures to maintain an idealized public image.” In this context, the lack of labor regulations of content made on social networks by minors

the poor compliance with existing guidelines means that these children can spend hours making monetized videos: “If these same 10-year-olds were working as waiters instead of influencers, they would be immediately penalized,” says the expert.

The Spanish National Cybersecurity Institute points out that the parents must also make sure that their children avoid personalized advertising on social media. They must set up the “ad configuration of the main social networks and use the options to report or denounce those advertisements that do not seem appropriate. Furthermore, it is very important that minors do not share personal information without the advice of a responsible adult, even if it seems like a trivial giveaway,” something very common on Instagram and TikTok. In addition, they see it as essential to “limit screen time in order to reduce the number of hours in which they will find advertising, therefore reducing the amount of commercial content that they will consume.” EL PAÍS

Youth, AI, Cryptocurrency and Greed

“Cyberattacks cost the world $945 billion a year.”

« Around the planet, crime is rising and the “bad guys” are ahead when it comes to cutting-edge technology. Financial institutions are the main target and geopolitics has become a process of extracting money, creating misery and jeopardizing the future. »

“Beyond the monetary damage, financial crimes affect human dignity.”

“Despite the official story, artificial intelligence (AI) is extremely fragile. Human beings are, too.”

“Youth, cryptocurrencies and greed are three key parts of modern economic crises. Despite a certain level of improved regulations, tax havens continue to operate. Meanwhile, cyberattacks _according to the Center for Strategic and International Studies — cost the world $945 billion a year. Financial institutions allocate around $214 billion annually to protect themselves as a result. The investment bank Goldman Sachs warns of how “tremendously destructive” a digital attack could be on the electrical grid of the Northeastern United States. Some 15 states would be left in darkness, while the price of this luminous Armageddon would range between $250 billion to $1 trillion in damages. Despite the official story, artificial intelligence (AI) is extremely fragile. Human beings are, too.

Corruption costs Latin America an astounding $200 billion annually. A 2017 survey from Transparency International interviewed 164,000 people around the world. About 25% claimed to have paid bribes in the previous year — something that’s responsible for about half of the global economic slowdown. Meanwhile, circumventing ethics and committing environmental crimes — such as illegal logging or mining, the third-largest type of criminal activity on the planet — generate $281 billion a year in profits. There’s a widespread idea that these crimes are “low risk, high return.”

The amount of money that has left sub-Saharan Africa illicitly since 1980 exceeds $1.3 trillion. This scarcity engenders greater poverty, more illegal immigration, environmental degradation, fewer external resources, reduced confidence in financial institutions, and increased inequality. The geopolitics of making the poor more miserable carries the risk of spreading anger across the continent.

The great beneficiary of this situation (along with Russia) is China. The Asian giant is the largest lender to nations on the African content (although Beijing never reveals the amount of debt) and, without a doubt, is the biggest external power in the region.

Around the planet, crime is rising and the “bad guys” are ahead when it comes to cutting-edge technology. Financial institutions are the main target and geopolitics has become a process of extracting money, creating misery and jeopardizing the future.

As a result of the fraudulent and the unfair, Europe — according to Mark Bou, head of communications at the Tax Justice Network — loses $181 billion in taxes annually, because billionaires and large companies use them to pay less than they should. This is equivalent to almost 12% of public health spending in European nations.

“A multi-billion-dollar industry has emerged in the world, employing some of the best-educated people as lawyers, consultants, accountants, with the sole purpose of evading taxes for the rich and the unscrupulous. And, yes, additionally, certain successful entrepreneurs avoid paying,” Daron Acemoğlu reflects. He’s professor of economics at MIT and a recurring candidate for a Nobel Prize. “Tax havens are particularly useful for people who have misbegotten wealth, due to bribery, embezzlement and manipulation. It’s a big problem.” The dark soul of abused talent. He warns: “[It’s] clearer than ever, with the Russian invasion of Ukraine, that these financial crimes are also costing lives.”

Few seem to care. The United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Ireland and Switzerland enable some of the biggest tax abuses on the planet. Europe as a whole is responsible for the loss of $236 billion annually in taxes, according to the Tax Justice Network. “In the Old Continent, in recent years, a growing flow of money of illicit origin from Russia and Malta has been detected,” reveals Enric Olcina, a partner at FS Consulting and head of Financial Crimes at KPMG in Spain. “Avoiding taxes is a permanent temptation. It’s inevitable and the reality is that [companies and millionaires] go where they pay less,” affirms jurist Antonio Garrigues Walker.

“It’s a problem without a solution. There will always be jurisdictions that offer tax incentives,” shrugs Mauro Guillén, vice dean of the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania.

The pessimism of the philosopher Emil Cioran (1911-1995) remains: “It’s not the violent evils that mark us, but the dull evils, the insistent, the tolerable ones, those that are part of our routine and meticulously undermine us, just like the time.”

In 2021, more than 140 countries and territories agreed to apply a minimum tax of 15% on the profits of multinationals. This “historic milestone” — as it was described at the time — is, today, thanks to legal loopholes, actually around 9%. “The financial crimes that cause the most damage to our states and societies are generated because they’re legal. The laws are written by the economic criminals’ own lawyers.”

In the EU, there are 30 special tax regimes that benefit 262,999 people with a tax cost of $7.5 billion euros ($8.2 billion) annually. The effective tax rate for billionaires in France is close to 0%. In the United States, it’s around 0.5%. A global 2% rate on the assets of these “lucky ones” (2,757 people, according to data published by the EU Tax Observatory in December 2022) would raise $214 billion. While it’s fiscally legal to wake up in a tax haven, perhaps a moral bridge is required to get over the greed. This is according to Mauro Guillén and Garrigues Walker. “Financial crimes limit the resources available to promote social development, such as [in the fields of] education and health,” warns Luis Ayala, a professor of economics at Spain’s National University of Distance Education. Crime makes the globe go round.

The National Crime Agency (NCA) estimates that there are at least 59,000 people in the U.K. involved in organized crime — including financial crimes — and the cost to the country is more than £47 billion ($59 billion) per year. Without these funds, generations are lost in precariousness, while money is wasted on drugs or luxuries. “Financial crimes have a devastating effect on economies and negatively contribute to the creation of differences between different social groups, since they’re linked to obtaining wealth through illicit activities. In many cases, [these activities] have a price in human lives, [because of] human-trafficking or drug-trafficking,” observes Manuel Delgado, a partner at EY.

Europe has always privileged regulation over a laissez faire system. The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) and the more recently-created Anti-Money Laundering Authority (AMLA) are Brussels’ containment dams. For this reason, financial institutions allocate $214 billion a year to protect themselves. “The reputational impact [that] an accusation of money laundering [has on] a bank is devastating. They’re very aware and are very careful with the clients they accept from territories considered to be tax havens or that have a bad reputation,” warns José García Montalvo, professor of Applied Economics at Barcelona’s Pompeu Fabra University (UPF). The 2015 closure, due to its illicit activities, of the Banca Privada de Andorra (BPA) is still vivid in his memory. Banco Madrid also disappeared. Coincidentally, the Madrid-based entity had its headquarters in Margaret Thatcher Square. The British prime minister — who, during her tenure from 1979 until 1990, deregulated the financial markets — pushed policies that contributed to the 2008-2009 financial crisis. Ironically, despite the increase in financial crimes, the scrutiny is greater.

The term “pig butchering” comes from China. It refers to the practice of gradually stuffing the animal (“fattening the pig”) before taking it to the slaughterhouse. In pig butchering scams, victims are pampered for quite some time. Upon being seduced (the targets are usually men), the scammers control their victims’ money through investments in cryptocurrencies, which at first offer great returns. However, later on, the beautiful financial advisor disappears with the funds into the deepest part of the internet. “The key is financial education: it’s the pillar of this decade,” explains Fernando de Rojas, a professor of economics at the Carlos III University in Madrid.

However, beyond the monetary damage, financial crimes affect human dignity. “This is as big a scandal as any of the financial scandals that we’ve seen in the last 20 years,” says Graham Barrow, an anti-money laundering expert. “It is an abject failure by the U.K. government to have done nothing about it.” It all started in China back in 2019, but it’s now making its way through Europe and the United States, where the FBI has already received complaints worth around $429 million.

Young people have — without a doubt — been attracted to the phenomenon of digital currencies. Cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin have three key purposes: to diversify savings portfolios (the United States has approved exchange-traded funds, or ETFs, amid this exchange of intangible currencies), to preserve capital in countries with corrupt governments (which often seize tangible assets) and to facilitate illicit activities. They make up the blackjack of financial capitalism. “Criminals won’t give up on the misuse of cryptocurrencies anytime soon,” predicts Jean-Philippe Lecouffe, deputy executive director of Operations at Europol.

Cheating has become so banal that they even dare to do so with JP Morgan Chase. Charlie Javice — an entrepreneur — created a startup called Frank, which she described as the “Amazon of higher education.” The platform helped students find funding for their degrees. On LinkedIn, she wrote that her platform had more than five million students and about 6,000 universities. The future was so bright that JP Morgan bought the company in 2021 for $175 million. But everything turned out to be false: Frank barely had 300,000 clients. Javice, 31, had (allegedly) hired a data scientist to fatten the numbers.

JP Morgan has 240,000 employees. The investment bank’s CEO earns $34.5 million a year for his expertise. Was everyone too busy to pay attention? Meanwhile, Javice denies the charges that have been levied against her. She’s facing up to 30 years in prison if convicted.

American executives should have been in front of their computers learning the latest information about AI or machine learning technology when this hoax occurred. The consulting firm McKinsey reports that “the techniques used to discover tax evasion are becoming more complex every day.” Big banks have invested $214 billion annually to protect themselves. American consulting firms trust in new technology: they feed their models with data about money laundering, illicit trafficking and terrorist financing, so that the technology learns to detect them. The red light flashes in real time. “Logically, if you’re able to design algorithms that prevent a good part of financial crimes, you’ll be helping to avoid them,” Enrique Dans confirms. He’s professor of innovation at the IE Business School in Madrid.

The big problem, however, lies within human beings. “We were, by nature, children of wrath, like the rest of mankind.” Ephesians 2:3. This tension haunts man more than 2,000 years later. According to data from the U.N., Latin America and the Caribbean account for half of the intentional homicides in the world, despite only representing 8% of the global population. The murder rate has increased in Central America and the Caribbean by 4% in the last two decades. And poor countries like Jamaica or El Salvador must allocate 2% of their wealth to combat crime. Loss of life results in a loss of prosperity. In Latin America, an increase in the homicide rate by 30% means a reduction in GDP growth by 0.14 percentage points. If the region had the same homicide rate as the global average, GDP would increase by 0.5% annually.

Financial crimes aren’t merely digital numbers traversing complex networks. The destruction of land and ecosystems is one of the most profitable “businesses” on the planet. Environmental crimes generated between $110 and $281 billion in criminal profits in 2021, according to the Financial Action Task Force (FATF). Illegal logging alone resulted in profits of $152 billion. And this represents much more than illicit money: it subtracts social and economic development, negatively impacts health and the environment, all while reducing the security of communities. Corruption is also encouraged, due to the links between illegal extractive industries with drug-trafficking and forced labor.

This dirty money takes advantage of financial secrecy laws, which criminals use to hide their identities, facilitate operations and launder the proceeds of crime. Investigations by the InSight Crime platform suggest that the problem is even greater, as the drug-trafficking and money-laundering networks grow in Brazil, Colombia, Peru and Ecuador. To the north, in Mexico — in the Sierra Madre Occidental, the mountains in the state of Chihuahua — the Tarahumara (or Rarámuri) Indigenous group has been inhabiting the territory for 15,000 years. But they have a problem: the area has become one of the main logging areas in the country, with drug-traffickers cutting down thousands of trees.

Without this forest, the sheep — the Tarahumara’s means of existence — will disappear. The women weave blankets out of their wool to protect their families from the freezing temperatures that descend over the mountains in winter. This material also provides for mortuary shrouds.

“They have stolen their arewá (soul),” laments Sofía Mariscal, who, through the Marso Foundation, tries to protect the dignity of the locals. “They want to take everything / Leave my land with nothing / My family suffers from hunger / My forest suffers from logging,” sing the Raprámuri, against a future of cement. “Seizing illicit funds and physical assets related to deforestation isn’t just about punishing criminals and demonstrating that ‘justice is done,’” says Juhani Grossmann, director of the Green Corruption program at the Basel Institute on Governance (Switzerland). “It’s also essential to prevent future deforestation, since by doing so, you prevent funds from being reinvested in this activity.”

Without the oxygen provided by the Amazon, the planet becomes a chronically ill person unable to exhale. Of the more than 300 operations carried out by the Brazilian Federal Police to combat environmental crimes in the Amazon — according to Melina Risso, research director of the Igarapé Institute — 30% involved fraud, 64% involved the bribing of officials and 61% involved money-laundering. The crime was based on four elements: illicit agriculture, the invasion of publicly-owned lands, illegal logging and clandestine mining.

With gold exceeding $2,000 per ounce (28.34 grams), the temptation of illegal exploitation has become irresistible in several Latin American countries. “Its nature — and the way it’s refined — make it very easy to hide the fact that it’s been illegally extracted,” Grossmann warns. Minerals critical for the green transition have also entered the picture. When state-owned companies participate, the risk of corruption increases, with more politicians and fewer justified expenses. “Nothing is in vain and that’s why I migrate / I also flee because I’m in danger / This is my soil, this is my air / And I don’t understand why they separate me / From that greed that invades them.” More verses against inequality from the Rarámuri people.

Daron Acemoğlu, from MIT, is spending his summer vacation in Turkey, his homeland. He walks through Istanbul — the city where he was born, in 1967 — and notes that inflation is around 65%. Concerns about the economy are discussed in cafés and shops. Acemoğlu is very sensitive to injustice. “One of the main failures of our era is that new technologies, globalization and integration increased productivity and generated economic growth (although not as much as some experts predicted), but [the gains] haven’t been shared. Inequality has increased. What’s more serious is that hundreds of millions of people have been left behind,” he reflects.

“Many believe the game is ‘rigged.’ Elites and technocrats have reorganized the economy [in a way that] has been biased against [the general public]. This belief is at the root of populist parties and leaders. It has reduced support for democracy across Europe.”

It’s certainly not a nonsensical thought, especially when you think of an isolated town in Wisconsin, or the prostitutes who walk Figueroa Street in Los Angeles. “Conspiratorial thinking is fanciful,” Acemoğlu sighs, “but many inequalities have been created by flawed policies and legal loopholes. [The technocracy] has also ignored the situation of the less educated and hasn’t done much to address inequality and inequalities. There’s no better place to see this than in dozens of tax havens around the world and the financial crimes they engender.” These havens are reserved for the few, while they represent a descent into hell for millions of other human beings.”

Miguel Ángel García Vega

El País

When the Scientists Cross the Red Lines

A group of Chinese scientists have cloned a monkey, one step closer to cloning humans

The 1996 cloning of Dolly the sheep caused a worldwide alert about the possibility that a laboratory might try to make clones of human beings. Then the first calves and mice were cloned in 1998, followed by goats in 1999, pigs in 2000, rabbits in 2002 and dogs in 2005. In 2007, the United Nations University published a report stating that the cloning of human beings was, perhaps, inevitable.

Andres Gambini emphasizes that the technique is still complex and has low efficiency rates. “Human cloning for reproductive purposes continues to be the subject of intense questioning, and not only because the technique is inefficient, involves embryonic and fetal death, and the physical and mental health of the clones is not guaranteed. What is the purpose of creating people through cloning? All the answers involve some legal, ethical or moral dilemma,” he says.

“Last week a team of Chinese scientists announced the birth of Retro, a macaque cloned with a new strategy to obtain identical monkeys. The 1996 cloning of Dolly the sheep caused a worldwide alert about the possibility that a laboratory might try to make clones of human beings. The technique seemed simple. British embryologist Ian Wilmut’s group emptied an egg from a sheep and inserted a nucleus with DNA from an adult cell taken from another female’s udder. Dolly was a replica of the latter.

The first calves and mice were cloned in 1998, followed by goats in 1999, pigs in 2000, rabbits in 2002 and dogs in 2005. In 2007, the United Nations University published a report stating that the cloning of human beings was, perhaps, inevitable.

Over two decades ago, some irresponsible scientists, such as Severino Antinori and Panos Zavos, even announced the imminent birth of cloned humans, but the reality was that Dolly’s technique — called somatic cell nuclear transfer — did not work well with primates, the animal group that includes monkeys and humans. That situation changed in 2018, when the same Qiang Sun team announced the birth of the first monkeys cloned using this strategy: two female crab macaque monkeys christened Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua. The word zhonghua means “Chinese nation.” At the time, one of the study’s co-authors, Poo Mu Ming, declared in this newspaper that “there are no barriers to cloning primates, so human cloning is closer to becoming a reality.”

The 2018 experiment was extremely inefficient. Qiang Sun and colleagues created 109 embryos, transferred 79 of them to 21 females, and achieved just six gestations. Only two monkeys were born. In the new study, published last week in the Nature Communications Journal, the researchers improved the technique by adding placental precursor cells. This time they created 113 embryos, transferred 11 of them to seven females and achieved two gestations and a single birth: a male rhesus macaque monkey, who is now three and a half years old. “This new strategy has significantly improved the efficiency of monkey cloning, both with respect to the number of embryos transplanted and the number of pregnant females used,” says Sun.

The Chinese researcher explains that they named the animal Retro, after the acronym for replacement of the trophectoderm, the layer of cells that gives rise to the placenta. “Retro is growing and getting stronger every day. He lives in our animal house with ample space and sunlight,” says the Chinese scientist, the director of the non-human primate facility at the Center of Excellence in Brain Science and Intelligence Technology in Shanghai.

German bioengineer Angelika Schnieke, one of the people involved in cloning Dolly the sheep, was concerned about Qiang Sun’s first experiments, which required dozens of pregnant females and largely resulted in miscarriages and malformed fetuses. “These cloned primates in China have crossed an ethical line. What is being done probably needs to be reconsidered,” Schnieke told EL PAÍS in 2018. “I personally find it hard to justify cloning monkeys. I worry that monkey cloning will continue and spread to other species,” she said at the time.

Qiang Sun argues that the use of monkeys is “essential” in the field of biomedical and cognitive research. In 2019, his team employed the technique already used with the Zhong Zhong and Hua Hua monkeys to create five clones of a crab macaque that had been genetically modified to mimic schizophrenia-like symptoms. Sun contends that these uniform populations of laboratory monkeys can be very useful for studying genetically based diseases, such as cancer and many brain disorders. His new study boasts of “introducing a promising strategy for cloning primates.”

Cloning is already routine in other species. Argentine veterinarian Andres Gambini first cloned horses in South America in 2010. He is currently doing research at the University of Queensland (Australia) and is the scientific director of Ovohorse, a Spanish company based in Marbella that offers “cloning services for dogs, cats, camels and horses, among animals.”

Gambini believes that Retro’s birth is “a remarkable advance” in the field. In his opinion, the study’s fundamental idea — replacing the placenta of cloned embryos with that of embryos created through in vitro fertilization — is not conceptually new, but its success shows an alternative for improving the efficiency of cloning. The Argentine veterinarian notes that this approach could also be used to implant embryos from an endangered wild animal into the uterus of females of similar domestic species. In 2020, his team succeeded in creating cloned zebra embryos from emptied mare ovaries.

Andres Gambini emphasizes that the technique is still complex and has low efficiency rates. “Human cloning for reproductive purposes continues to be the subject of intense questioning, and not only because the technique is inefficient, involves embryonic and fetal death, and the physical and mental health of the clones is not guaranteed. What is the purpose of creating people through cloning? All the answers involve some legal, ethical or moral dilemma,” he says.

The Universal Declaration on the Human Genome and Human Rights prohibits human cloning and was adopted by the United Nations in 1998. Dutch jurist Bartha Knoppers, who participated in drafting the document, does not believe that anyone would dare to take the step, not even a megalomaniac dictator. “I think human reproductive cloning is one of the areas where there is a virtually universal consensus that we should never go down that road,” she explained in an interview with EL PAÍS just over a year ago. “It would create an element of industrialization in reproduction and turn people into things that can be copied. For me, it’s a red line.”

EL PAÍS

When you eat is as important as what you eat

If you eat at the wrong time, none of the organs that prepare to receive the food react well.

The body is programmed a certain way, and the organs function accordingly.

A mismatch between the time of meals and the human body’s biological clock increases the risk of diseases because many organs function on a schedule

“There are more than 300 identified genes that define the predisposition of each individual to be more of a morning or evening person.”

“The way you eat is essential for your health. But not only what and how much we eat have an influence, but also when we eat. In recent years, science has focused on unraveling the phenomenon of chrononutrition which explains the relationship between time-related eating patterns, circadian rhythm, and metabolic health. And research has already shed light on the importance of food intake times that are synchronized with our circadian rhythm, which is the 24-hour biological clock that regulates internal physiological functions. For example, scientists have discovered that skipping breakfast is associated with a higher risk of obesity, and eating late dinners is also linked to weight gain.

Humans have a kind of central clock that sets the time for the body. At first glance, it is a barely one-millimeter ball located in the hypothalamus, but these tiny molecular devices are capable of telling the time to the rest of the body. Together with the small chronometers that are independent of the tissues, they anticipate and prepare the cells for what is to come, such as eating at noon or going to sleep at night. “Our body has schedules and this central clock is not isolated, but is synchronized with the outside world, mainly through light and darkness, but also with changes between eating and fasting or with periods of activity and rest,” Marta Garaulet, a professor of Physiology at the University of Murcia and expert in chrononutrition explains.

Keeping to our circadian rhythm and all the biological changes that follow a 24-hour cycle is essential for health. So much so that a disruption in these biorhythms can alter basic vital functions, the scientist points out: “We are made to sleep at night and we do not eat while we sleep. We are made to eat and move during the day. So, if your body perceives that there is light at night or that you are eating, it is receiving contradictory information.”

Internal biorhythms are regulated through the central clock, peripheral chronometers (which are in organs and tissues), lifestyle habits, behaviors, and the environment. “A person who is in good chronobiological health is one who has all their clocks synchronized in accordance with the changes of light and darkness,” Garaulet says. Now, there may be synchronization failures in the central clock, in the peripherals or in the behaviors, and that can create chronodisruptions that, in the long run, “are related to diseases, such as obesity, cancer, depression, or metabolic alterations,” says the scientist. “This is clearly seen in shift workers or employees who work at night, people whose behaviors are misaligned with their internal clock.”

The body is programmed a certain way, and the organs function accordingly. That is, in a different way during the 24 hours of the day: they do not respond in the same way if they have to work at a time that they had not planned. The pancreas, for example, is lazier at night and more active during the day. “Eating dinner late has a very clear effect: it coincides with the secretion of melatonin, which is the hormone that prepares you for sleep, with insulin, which is the hormone that helps distribute food. But, in the presence of melatonin, insulin secretion is reduced and tolerance to sugar and carbohydrates is worse,” says the chronobiologist. She and her team discovered a decade ago that eating late can influence your ability to lose weight when you’re on a diet.

Lidia Daimiel, researcher at the Madrid Institute of Advanced Studies and the Obesity and Nutrition Network Research Center, insists that “the body is not equally prepared to manage food at just any time of the day.” For this reason, when you eat is a determining factor in the chronobiology of an individual, she explains: “When you eat is as important as what you eat. If what you eat is good and healthy, but the timing is not right, you are not getting the benefit at the same magnitude that that food could give you.”

In practice, there can be an impact on overall health. “Once the time is set, it can affect everything,” says Garaulet.The recent studies indicating that chronodisruptive eating behaviors “have been implicated in many health disorders, including sleep disorders, cardiometabolic risk, unbalanced energy distribution, deregulation of body temperature, weight gain, and psychosocial discomfort,” among others.